Good old Johan Zacharias Blackstadius; he just doesn’t get the credit that he deserves. It probably doesn’t help that his name doesn’t quite roll off the tongue with the same grace and ease of, say, a “John Bauer,” a “Gustaf Tenggren,” or a “Jenny Nyström.” Nor does it help that his contributions to the canon of Nordic historical/folkloric/mythical artwork never really made as much of a splash or set the same standards for others to blatantly admire and emulate as that of those other artists. But nonetheless, he gave us some solid works that depict relevant themes when he wasn’t too busy restoring church frescoes or painting portraits of prominent Swedish men or ruins nestled in Mediterranean landscapes.

So, most of his work does not relate to the themes pertinent to this mediocre blog, but those that do, like Två bondflickor som lyssnar till Strömkarlens spel (“Two Peasant Girls Listening to the Playing of the Water-Sprite”) as pictured at the top of this page, provide some good, clean fun for the Nordicly nerdy-minded. Housed at Sweden’s Nationalmuseum, this oil painting is rather obviously inspired by the seductive Swedish folkloric being known as a strömkarl (or fossegrim), a particularly morose and somber relative of the more malevolent näcke (or neck/nixie). He plays his fiddle for food, and sometimes teaches his listeners the intricacies of the instrument, as well. That’s a much friendlier mystical encounter than the sort that tend to occur with his brethren necks/nixies, which usually result in a mean-spirited drowning incident.

Another fun Blackstadius outlier is his Kalevala-inspired Väinämöinen kiinnittää kielet kanteleeseen (“Väinämöinen Attaches Strings to his Kantele”), which illustrates the great Finnish mythological hero Väinämöinen as he creates a replacement kantele from a birch tree after having lost his first one, which was of course constructed from the jawbone of a dead giant fish.

Blackstadius also created a series of drawings that feature the always-popular motif of witchy women floating in the air. Perhaps these drawings provided a creative and emotional outlet to counterbalance the rampant portraits and church restorations? We’ll probably never know, and this isn’t the type of place to dig to that level of detail anyway.

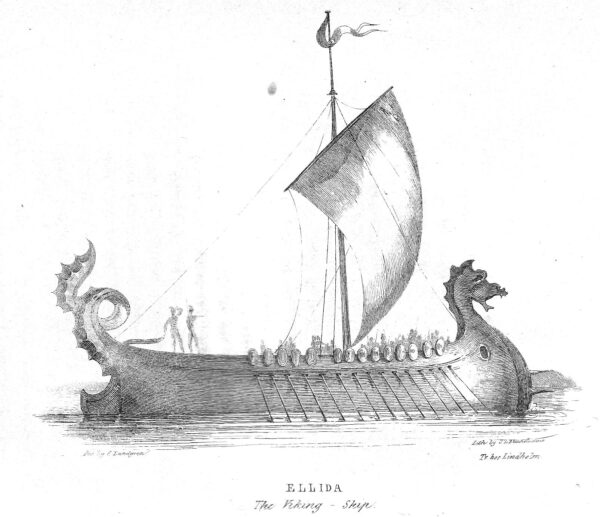

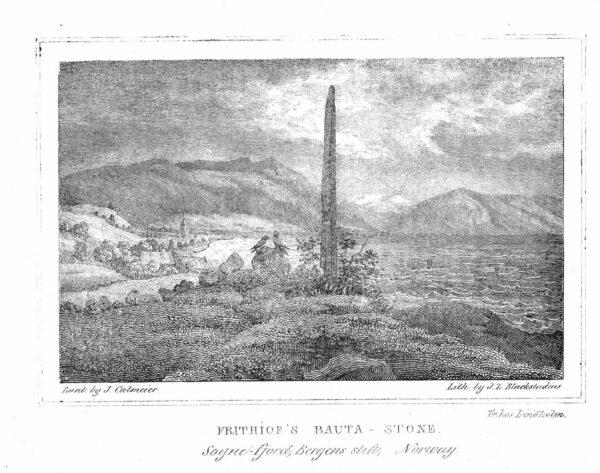

But most relevant for this mediocre blog is his work as a lithographer, because he illustrated Esaias Tegnér’s epic poem, Frithiof’s Saga, which was based on a legendary Icelandic saga of the same name. Written over the course of five years, Tegnér published the completed version in Swedish in 1825 and Blackstadius provided the interior illustrations. This saga-turned-poem proved to be hugely popular, particularly in Sweden, and has been translated to many other languages. It also served as an inspiration for paintings by both August Malmström and Peter Nicolai Arbo. Blackstadius’ drawings were included in the actual print edition of the volume, and have been preserved for posterity’s sake online at Project Runeberg should anyone out there feel the need to peruse all of them (click the links labelled “Bild” if you choose to go down this rabbit hole and can’t read Swedish).

And then, in the end, Blackstadius died. This occurred in 1898 in Stockholm after a long life full of art creation of various sorts, some pieces clearly more interesting than others. If you want to know more about him from an official source, and can read Swedish, then check out this page from Sweden’s Riksarkivet. Otherwise, Wikipedia will do you a solid, too.